The Macabre Case of the Twins Who Married Each Other and Created Their Own Dynasty (Oregon, 1903)

In the remote mountains of Oregon, where the pines rise like spires and daylight struggles to reach the forest floor, an old story still circulates in whispers. It’s a legend so unsettling that even the locals near Crater Lake prefer to call it “the thing that happened in the Oats house” — as if naming it could somehow summon it again.

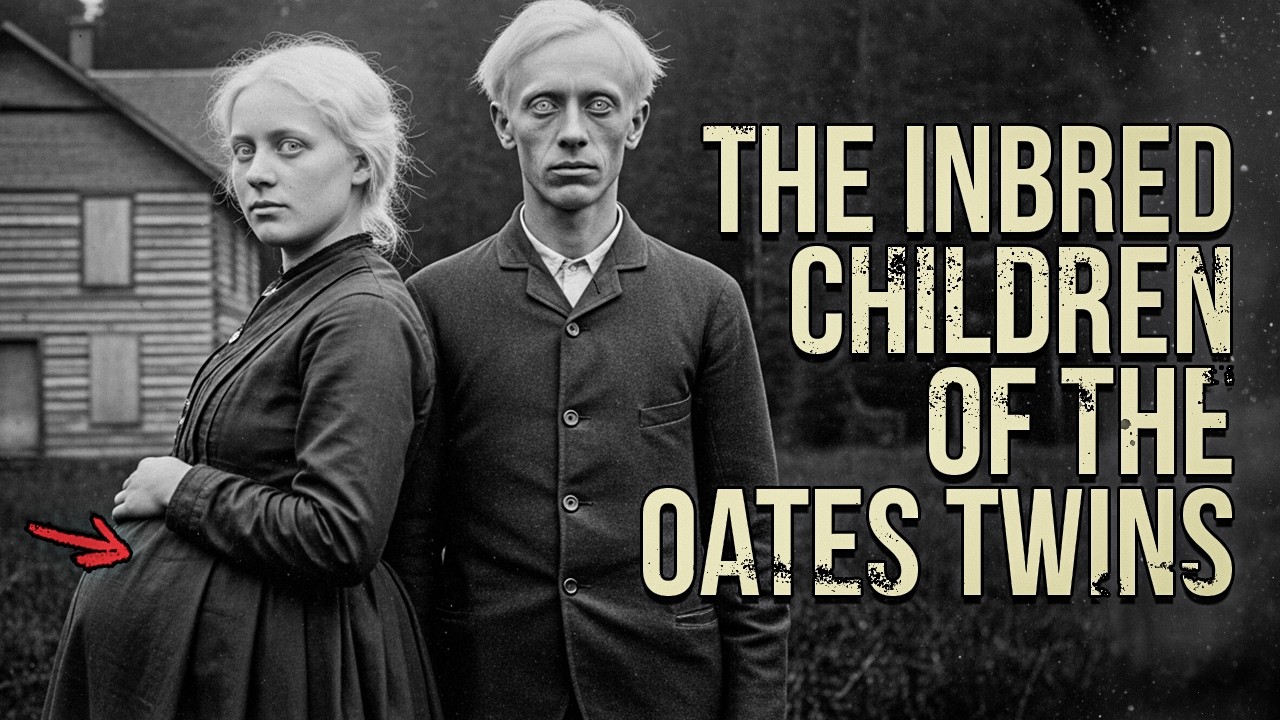

Between 1903 and 1913, on a stretch of land fifteen miles from the nearest town, a family of loggers became the center of one of the most grotesque and secretive sagas in Oregon’s history. At the heart of the story were two twin siblings — Phoebe and Wilbert Oats — whose twisted bond defied morality, law, and nature itself.

What began as an eccentric family’s retreat into isolation ended in horror: a secret marriage, six children born of incest, multiple disappearances, and a basement that investigators later described as “a chamber of human experimentation.”

The House in the Pines

The Oats property was built in 1885 by Waldo Oats, a timberman with ambitions of founding a lumber dynasty. When his wife died giving birth to twins, he devoted himself to raising them alone amid the vast Oregon wilderness.

The children — pale, flaxen-haired, and eerily identical — grew up in near-total isolation. Visitors to the property described the siblings as inseparable, communicating through glances more than words. After a traumatic trip to town, where young Phoebe was mocked for her ghostly complexion, Waldo withdrew them completely from society.

By 1902, when the twins turned eighteen, even the mail carriers rarely approached the Oats gate. Inside the weather-beaten house, Phoebe and Wilbert developed habits that unsettled their father: long hours locked in the attic, whispered conversations in a private language, and a growing fascination with their late grandfather’s books — old treatises on heredity, breeding, and “pure bloodlines.”

Then came the announcement that no father could have imagined.

“We’ve Chosen Each Other”

In early 1903, Phoebe and Wilbert calmly informed their father they planned to marry — not to outsiders, but to one another.

Waldo thought it was a sick joke. But the twins, with unnerving composure, explained they’d studied examples of “noble families preserving their lineage” and saw no moral difference in uniting themselves. Their logic was cold, academic — the language of people who had replaced affection with obsession.

The “ceremony” took place on the Oats property that May. No pastor, no guests — just the twins, dressed in white, and a father forced to witness the unthinkable. The marriage, though never legally recognized, bound them together in mind and purpose. From that day forward, they sealed the property off from the outside world.

Neighbors noticed changes: new locks on doors, boarded windows, smoke from the chimney at strange hours. Waldo began hearing noises beneath the floorboards. And in March 1904, the first of the Oats children was born.

The Children of Silence

The first child — a girl — was delivered during a violent storm. When Waldo saw her, he froze in horror. The baby’s skull was misshapen, her hands bore extra fingers, and her breathing was shallow.

To his astonishment, Phoebe and Wilbert reacted not with grief but pride. “She’s perfect,” Phoebe reportedly murmured. “Exactly as we hoped.”

Within months, the Oats twins conceived again. The second child, born later that year, appeared healthy. But instead of relief, the parents seemed disappointed. They doted on the deformed daughter while neglecting the normal son — a pattern that continued through each subsequent pregnancy.

By 1905, rumors began to spread through Crater Lake. Locals whispered that the Oats twins rarely came to town but ordered strange supplies: lime, heavy rope, and limewash for “preserving” the basement. Some nights, travelers swore they saw lights flickering through the boarded windows and heard crying — the kind that doesn’t sound quite human.

Then a hunter named Homer Mixon decided to find out what was happening behind those locked doors.

The Hunter Who Never Came Back

Homer Mixon was a seasoned outdoorsman who had fought in the Indian Wars. In the summer of 1905, he visited the Oats property, pretending to be lost.

The twins welcomed him politely, offering coffee, but something felt wrong. There was a smell — metallic and antiseptic — and the sound of faint crying beneath the floor. When Homer mentioned it, the twins smiled in eerie unison and claimed it was “just the wind.”

He left unsettled but determined to return. Days later, he crept back at dawn, peering through a basement window. What he saw sent him fleeing into the woods — but he never made it out.

Three days later, his rifle was found leaning against a tree a mile from the Oats house. His body was never recovered.

After that, the people of Crater Lake stopped talking about the Oats family altogether.

The Doctor Who Followed the Sound

For nearly a decade, the twins lived undisturbed. Their father, Waldo, aged into a broken man, muttering about “children who shouldn’t exist.” A few townspeople noticed his deterioration, but none dared visit the property.

Then in 1912, a local physician, Dr. Clarence Benson, began asking questions. He had delivered one of Phoebe’s early children and knew there should be several more — yet only two births were ever registered.

Benson began observing the property from afar. Through binoculars, he saw the twins moving between the house and the basement, carrying buckets and blankets. He planned a formal investigation in December.

He never returned. His carriage was found overturned two miles away, horses still tethered, his medical bag open in the snow.

When asked, the twins expressed polite concern. But neighbors began whispering what everyone feared: anyone who entered that house did not come out.

The Search of 1913

In March 1913, Sheriff Skyler Tucker finally obtained a search warrant. Accompanied by two deputies, he rode to the Oats property on a fog-choked morning.

The twins greeted them calmly, even smiling. “We’ve been expecting you,” Wilbert said.

Inside, the air reeked of chemicals and decay. The upper rooms were covered in anatomical sketches, family trees, and handwritten notes about “generational refinement.” The children were listed by number, not by name.

In a locked attic room, deputies found a girl of about nine, emaciated and deformed, crouched in filth. “She screamed like an animal,” Tucker later recalled. “Not from fear — from habit.”

But the true horror waited below.

The basement was divided into small cells, each reinforced with metal doors. Inside them were the surviving Oats children — four in total — living evidence of nearly a decade of incest and experimentation.

One boy sat motionless, rocking back and forth. A younger girl’s wrists were raw from ropes. Another child lay dead, decomposing in straw. On the walls were scratch marks — hundreds of them — where small fingers had counted the days.

Among the scattered papers were meticulous “reports” documenting each child’s development, deformity, and death. In the twins’ own handwriting, phrases like “specimen three expired during test” and “subject shows promising cranial structure.”

The sheriff also found Homer Mixon’s knife and the doctor’s watch buried under a worktable.

When Tucker confronted the twins, they didn’t deny anything. Phoebe, expressionless, said, “Not all specimens survive. Observation requires sacrifice.”

Trial of the Century That Time Forgot

The Oats twins were arrested that day. Waldo, discovered locked in an upstairs room, was barely alive — starved, trembling, and muttering about “voices in the floor.” He died in an asylum five years later.

At their trial, Phoebe and Wilbert spoke eloquently, even proudly. They claimed they were conducting “a generational study of hereditary perfection.” Their notes, they argued, could “advance human knowledge.”

The jury took less than an hour to convict. Both were sentenced to life in prison. Phoebe died in 1934, still insisting she had “served science.” Wilbert outlived her by nearly two decades, dying behind bars in 1951 — unrepentant to the end.

The surviving children were placed in state care, but none recovered fully. One died young; another lived into adulthood but never spoke again.

In 1920, lightning — or perhaps the townspeople’s will — reduced the Oats house to ash. Nothing grew properly on the land afterward.

Echoes in the Pines

More than a century later, hunters still claim to hear cries drifting through the trees near the site of the old Oats property — the cries of children, or perhaps something less human.

To this day, no one knows how many children Phoebe and Wilbert produced in their self-made dynasty, or how many died in those basement cells. The official record lists six. Locals say there were more.

What remains certain is that isolation, obsession, and intellect — left to ferment unchecked — can curdle into something monstrous.

The Oats twins didn’t just commit crimes. They rationalized them. They convinced themselves that cruelty was curiosity, that parenthood was experimentation, and that love could be purified through blood.

Their story endures as one of the darkest reminders that horror doesn’t always come from ghosts or beasts. Sometimes, it grows quietly — in houses hidden by trees, among people who believe they are doing good.

In the mountains of Oregon, the forest still whispers their names.